Prairie Fire Organizing Committee (PFOC) emerged from the student, anti-Vietnam war and national liberation struggles of the 1960s and 70s. It began in 1975, following the Weather Underground’s publication of Prairie Fire: The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism in 1974. At its height in the 1980s, chapters existed in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Atlanta.

PFOC understood the United States as an empire based on white supremacy and white settler colonialism, which granted white people privilege and power over people of color. We believed that the fight for national liberation within and outside U.S. borders would be the key to overthrowing imperialism and building a socialist society. Solidarity with the movements for liberation, nationhood and self-determination of Black, indigenous, and Chicano/Mexicano people, and independence for Puerto Rico was, therefore, central to its politics.

PFOC understood the United States as an empire based on white supremacy and white settler colonialism, which granted white people privilege and power over people of color. We believed that the fight for national liberation within and outside U.S. borders would be the key to overthrowing imperialism and building a socialist society. Solidarity with the movements for liberation, nationhood and self-determination of Black, indigenous, and Chicano/Mexicano people, and independence for Puerto Rico was, therefore, central to its politics.

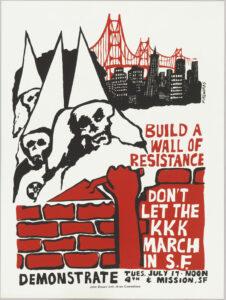

Taking leadership from organizations of color, PFOC believed it was its job to build anti-racism among other white people. It helped to found the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee, which participated in numerous campaigns to expose and fight the rise of white supremacist and neo-Nazi organizing, and to support the Black Liberation Movement.

Taking leadership from organizations of color, PFOC believed it was its job to build anti-racism among other white people. It helped to found the John Brown Anti-Klan Committee, which participated in numerous campaigns to expose and fight the rise of white supremacist and neo-Nazi organizing, and to support the Black Liberation Movement.

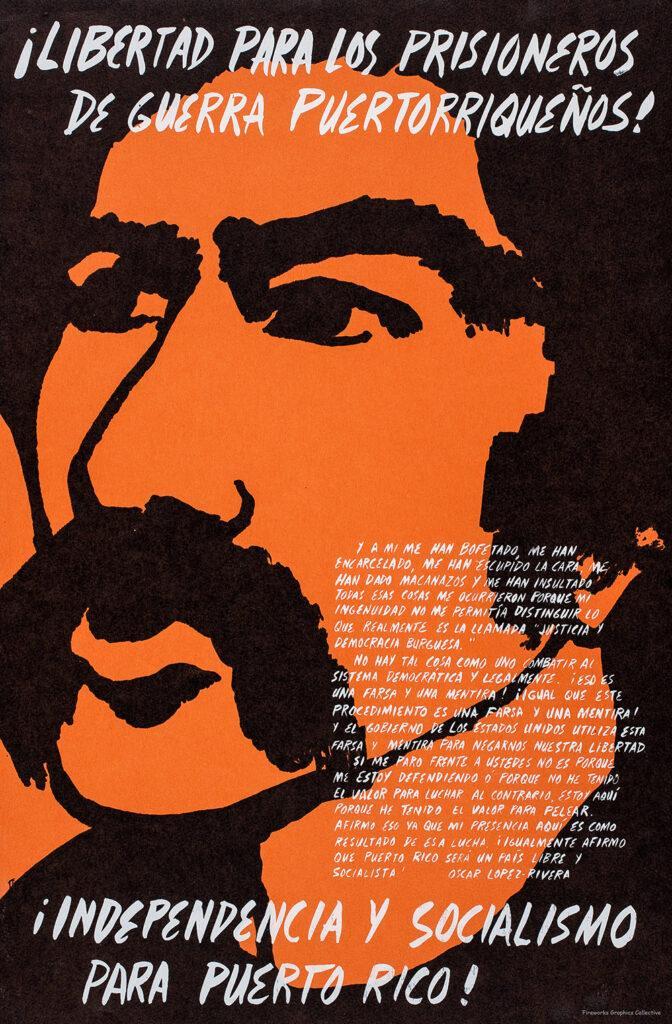

It also supported independence for Puerto Rico and freedom for the Puerto Rican political prisoners through the New Movement in Solidarity with Puerto Rican Independence in the late 1970s. It worked directly with the Movimiento de Liberación Nacional (Puertorriqueño), which was based in Chicago.

PFOC believed that the U.S. state would never reform itself, and gave political support to revolutionary armed movements both internationally and within the U.S. The freedom of political prisoners from those movements who were in prison, often for decades, was one of its central tenets. PFOC joined with other groups to fight for the release of all political prisoners to form Freedom Now! and helped facilitate two international tribunals on the subject of human rights in the US, held in 1991 and 1992.

PFOC believed that the U.S. state would never reform itself, and gave political support to revolutionary armed movements both internationally and within the U.S. The freedom of political prisoners from those movements who were in prison, often for decades, was one of its central tenets. PFOC joined with other groups to fight for the release of all political prisoners to form Freedom Now! and helped facilitate two international tribunals on the subject of human rights in the US, held in 1991 and 1992.

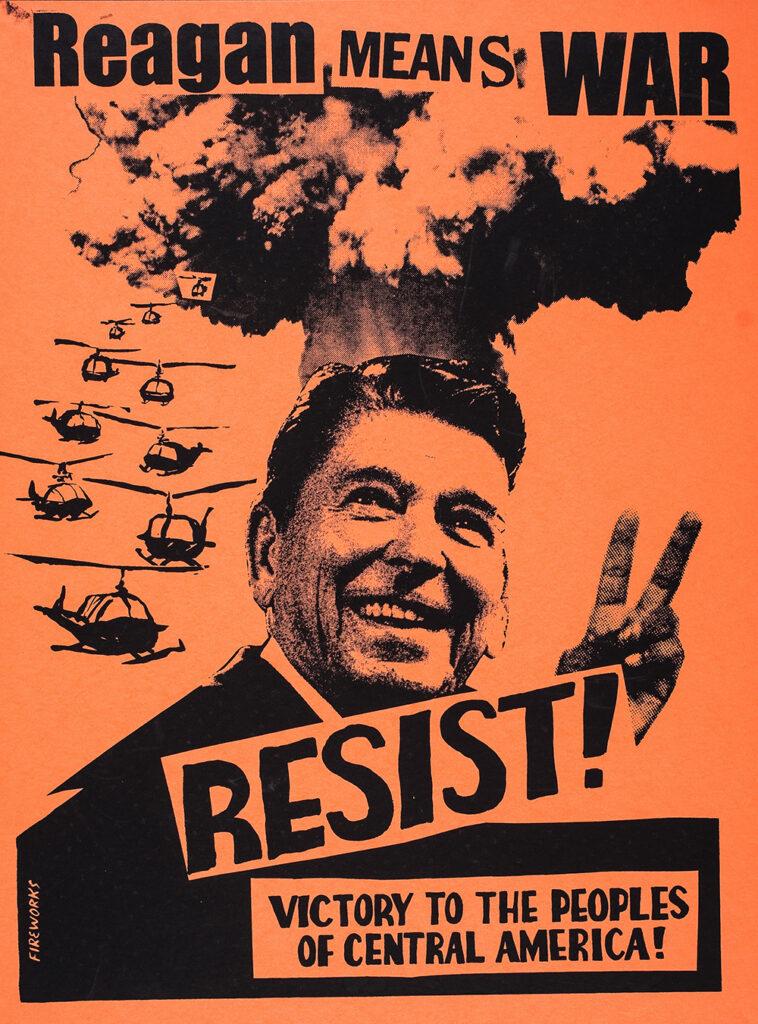

PFOC was internationalist. It worked to generate opposition to U.S. war and militarism and helped build movements in support of the liberation struggles in South Africa, Central America, Haiti, Philippines and Palestine. To that end it worked closely with revolutionary organizations from those nations and initiated or joined other North American individuals and organizations to build solidarity with them. For example, during the 1980s women in PFOC were instrumental in organizing the Woman-to-Woman Campaign, which supported AMES, the Association of Salvadoran Women in El Salvador, and AMNLAE, the Luisa Amanda Espinosa Association of Nicaraguan Women. Both organizations educated people in the United States about the needs and work of women in these two Central American countries and raised money to support their efforts. It also worked with GABRIELA, the national women’s coalition of the Philippines and supported the revolutionary movement there.

PFOC was internationalist. It worked to generate opposition to U.S. war and militarism and helped build movements in support of the liberation struggles in South Africa, Central America, Haiti, Philippines and Palestine. To that end it worked closely with revolutionary organizations from those nations and initiated or joined other North American individuals and organizations to build solidarity with them. For example, during the 1980s women in PFOC were instrumental in organizing the Woman-to-Woman Campaign, which supported AMES, the Association of Salvadoran Women in El Salvador, and AMNLAE, the Luisa Amanda Espinosa Association of Nicaraguan Women. Both organizations educated people in the United States about the needs and work of women in these two Central American countries and raised money to support their efforts. It also worked with GABRIELA, the national women’s coalition of the Philippines and supported the revolutionary movement there.

PFOC was a feminist organization. It saw male supremacy as a core component of capitalism/imperialism and believed that women’s liberation must be integral to any struggle for revolution. Women in PFOC helped start Women Against Imperialism and worked to support women’s liberation at home and abroad. As part of its commitment to women’s liberation, PFOC developed a collective childcare system to support women in the organization who had children. It also confronted men who exhibited male supremacist attitudes or practices to women, both within and outside the organizations. Challenged by its large number of lesbians and gay men within the organization, it also came to view queer liberation as vital and helped work to build the emerging LGBTQ+ movement. PFOC members were part of ACT UP and helped to create the Dyke March.

PFOC was a feminist organization. It saw male supremacy as a core component of capitalism/imperialism and believed that women’s liberation must be integral to any struggle for revolution. Women in PFOC helped start Women Against Imperialism and worked to support women’s liberation at home and abroad. As part of its commitment to women’s liberation, PFOC developed a collective childcare system to support women in the organization who had children. It also confronted men who exhibited male supremacist attitudes or practices to women, both within and outside the organizations. Challenged by its large number of lesbians and gay men within the organization, it also came to view queer liberation as vital and helped work to build the emerging LGBTQ+ movement. PFOC members were part of ACT UP and helped to create the Dyke March.

PFOC embraced a multi-level approach to organizing. It participated in broad coalitions, mass demonstrations, direct action, and political education.

PFOC embraced a multi-level approach to organizing. It participated in broad coalitions, mass demonstrations, direct action, and political education.

Its journal, BREAKTHROUGH, which was published from 1977–1994, reflected this approach in the breadth of its work and politics, as well as its commitment to art and culture. Fireworks, its art collective, produced posters in support of national liberation, against US militarism and for women’s and gay liberation. It also produced art against state repression. One Fireworks poster—SLAM, SLAM, SLAM: DON’T TALK TO THE FBI—is still being used 40 years after its original publication.

PFOC officially disbanded in the mid-1990s. Today, many of its former members remain very engaged and committed political activists, working in international solidarity, environmental, feminist, anti-racist, and LGBTQ+ movements.